Custom Renderer

Dioxus is an incredibly portable framework for UI development. The lessons, knowledge, hooks, and components you acquire over time can always be used for future projects. However, sometimes those projects cannot leverage a supported renderer or you need to implement your own better renderer.

Great news: the design of the renderer is entirely up to you! We provide suggestions and inspiration with the 1st party renderers, but only really require processing DomEdits and sending UserEvents.

The specifics:

Implementing the renderer is fairly straightforward. The renderer needs to:

- Handle the stream of edits generated by updates to the virtual DOM

- Register listeners and pass events into the virtual DOM's event system

Essentially, your renderer needs to process edits and generate events to update the VirtualDOM. From there, you'll have everything needed to render the VirtualDOM to the screen.

Internally, Dioxus handles the tree relationship, diffing, memory management, and the event system, leaving as little as possible required for renderers to implement themselves.

For reference, check out the javascript interpreter or tui renderer as a starting point for your custom renderer.

Templates

Dioxus is built around the concept of Templates. Templates describe a UI tree known at compile time with dynamic parts filled at runtime. This is useful internally to make skip diffing static nodes, but it is also useful for the renderer to reuse parts of the UI tree. This can be useful for things like a list of items. Each item could contain some static parts and some dynamic parts. The renderer can use the template to create a static part of the UI once, clone it for each element in the list, and then fill in the dynamic parts.

Mutations

The Mutation type is a serialized enum that represents an operation that should be applied to update the UI. The variants roughly follow this set:

enum Mutation { AppendChildren, AssignId, CreatePlaceholder, CreateTextNode, HydrateText, LoadTemplate, ReplaceWith, ReplacePlaceholder, InsertAfter, InsertBefore, SetAttribute, SetText, NewEventListener, RemoveEventListener, Remove, PushRoot, }

The Dioxus diffing mechanism operates as a stack machine where the "push_root" method pushes a new "real" DOM node onto the stack and "append_child" and "replace_with" both remove nodes from the stack.

An Example

For the sake of understanding, let's consider this example – a very simple UI declaration:

rsx!( h1 {"count {x}"} )

To get things started, Dioxus must first navigate to the container of this h1 tag. To "navigate" here, the internal diffing algorithm generates the DomEdit PushRoot where the ID of the root is the container.

When the renderer receives this instruction, it pushes the actual Node onto its own stack. The real renderer's stack will look like this:

instructions: [ PushRoot(Container) ] stack: [ ContainerNode, ]

Next, Dioxus will encounter the h1 node. The diff algorithm decides that this node needs to be created, so Dioxus will generate the DomEdit CreateElement. When the renderer receives this instruction, it will create an unmounted node and push it into its own stack:

instructions: [ PushRoot(Container), CreateElement(h1), ] stack: [ ContainerNode, h1, ]

Next, Dioxus sees the text node, and generates the CreateTextNode DomEdit:

instructions: [ PushRoot(Container), CreateElement(h1), CreateTextNode("hello world") ] stack: [ ContainerNode, h1, "hello world" ]

Remember, the text node is not attached to anything (it is unmounted) so Dioxus needs to generate an Edit that connects the text node to the h1 element. It depends on the situation, but in this case, we use AppendChildren. This pops the text node off the stack, leaving the h1 element as the next element in line.

instructions: [ PushRoot(Container), CreateElement(h1), CreateTextNode("hello world"), AppendChildren(1) ] stack: [ ContainerNode, h1 ]

We call AppendChildren again, popping off the h1 node and attaching it to the parent:

instructions: [ PushRoot(Container), CreateElement(h1), CreateTextNode("hello world"), AppendChildren(1), AppendChildren(1) ] stack: [ ContainerNode, ]

Finally, the container is popped since we don't need it anymore.

instructions: [ PushRoot(Container), CreateElement(h1), CreateTextNode("hello world"), AppendChildren(1), AppendChildren(1), PopRoot ] stack: []

Over time, our stack looked like this:

[] [Container] [Container, h1] [Container, h1, "hello world"] [Container, h1] [Container] []

Notice how our stack is empty once UI has been mounted. Conveniently, this approach completely separates the Virtual DOM and the Real DOM. Additionally, these edits are serializable, meaning we can even manage UIs across a network connection. This little stack machine and serialized edits make Dioxus independent of platform specifics.

Dioxus is also really fast. Because Dioxus splits the diff and patch phase, it's able to make all the edits to the RealDOM in a very short amount of time (less than a single frame) making rendering very snappy. It also allows Dioxus to cancel large diffing operations if higher priority work comes in while it's diffing.

It's important to note that there is one layer of connectedness between Dioxus and the renderer. Dioxus saves and loads elements (the PushRoot edit) with an ID. Inside the VirtualDOM, this is just tracked as a u64.

Whenever a CreateElement edit is generated during diffing, Dioxus increments its node counter and assigns that new element its current NodeCount. The RealDom is responsible for remembering this ID and pushing the correct node when PushRoot(ID) is generated. Dioxus reclaims the IDs of elements when removed. To stay in sync with Dioxus you can use a sparse Vec (Vec < Option

This little demo serves to show exactly how a Renderer would need to process an edit stream to build UIs. A set of serialized DomEditss for various demos is available for you to test your custom renderer against.

Event loop

Like most GUIs, Dioxus relies on an event loop to progress the VirtualDOM. The VirtualDOM itself can produce events as well, so it's important that your custom renderer can handle those too.

The code for the WebSys implementation is straightforward, so we'll add it here to demonstrate how simple an event loop is:

pub async fn run(&mut self) -> dioxus_core::error::Result<()> { // Push the body element onto the WebsysDom's stack machine let mut websys_dom = crate::new::WebsysDom::new(prepare_websys_dom()); websys_dom.stack.push(root_node); // Rebuild or hydrate the virtualdom let mutations = self.internal_dom.rebuild(); websys_dom.apply_mutations(mutations); // Wait for updates from the real dom and progress the virtual dom loop { let user_input_future = websys_dom.wait_for_event(); let internal_event_future = self.internal_dom.wait_for_work(); match select(user_input_future, internal_event_future).await { Either::Left((_, _)) => { let mutations = self.internal_dom.work_with_deadline(|| false); websys_dom.apply_mutations(mutations); }, Either::Right((event, _)) => websys_dom.handle_event(event), } // render } }

It's important that you decode the real events from your event system into Dioxus' synthetic event system (synthetic meaning abstracted). This simply means matching your event type and creating a Dioxus UserEvent type. Right now, the VirtualEvent system is modeled almost entirely around the HTML spec, but we are interested in slimming it down.

fn virtual_event_from_websys_event(event: &web_sys::Event) -> VirtualEvent { match event.type_().as_str() { "keydown" => { let event: web_sys::KeyboardEvent = event.clone().dyn_into().unwrap(); UserEvent::KeyboardEvent(UserEvent { scope_id: None, priority: EventPriority::Medium, name: "keydown", // This should be whatever element is focused element: Some(ElementId(0)), data: Arc::new(KeyboardData{ char_code: event.char_code(), key: event.key(), key_code: event.key_code(), alt_key: event.alt_key(), ctrl_key: event.ctrl_key(), meta_key: event.meta_key(), shift_key: event.shift_key(), location: event.location(), repeat: event.repeat(), which: event.which(), }) }) } _ => todo!() } }

Custom raw elements

If you need to go as far as relying on custom elements for your renderer – you totally can. This still enables you to use Dioxus' reactive nature, component system, shared state, and other features, but will ultimately generate different nodes. All attributes and listeners for the HTML and SVG namespace are shuttled through helper structs that essentially compile away (pose no runtime overhead). You can drop in your own elements any time you want, with little hassle. However, you must be absolutely sure your renderer can handle the new type, or it will crash and burn.

These custom elements are defined as unit structs with trait implementations.

For example, the div element is (approximately!) defined as such:

struct div; impl div { /// Some glorious documentation about the class property. const TAG_NAME: &'static str = "div"; const NAME_SPACE: Option<&'static str> = None; // define the class attribute pub fn class<'a>(&self, cx: NodeFactory<'a>, val: Arguments) -> Attribute<'a> { cx.attr("class", val, None, false) } // more attributes }

You've probably noticed that many elements in the rsx! macros support on-hover documentation. The approach we take to custom elements means that the unit struct is created immediately where the element is used in the macro. When the macro is expanded, the doc comments still apply to the unit struct, giving tons of in-editor feedback, even inside a proc macro.

Native Core

If you are creating a renderer in rust, native-core provides some utilities to implement a renderer. It provides an abstraction over DomEdits and handles the layout for you.

RealDom

The RealDom is a higher-level abstraction over updating the Dom. It updates with DomEdits and provides a way to incrementally update the state of nodes based on what attributes change.

Example

Let's build a toy renderer with borders, size, and text color. Before we start let's take a look at an example element we can render:

cx.render(rsx!{ div{ color: "red", p{ border: "1px solid black", "hello world" } } })

In this tree, the color depends on the parent's color. The size depends on the children's size, the current text, and the text size. The border depends on only the current node.

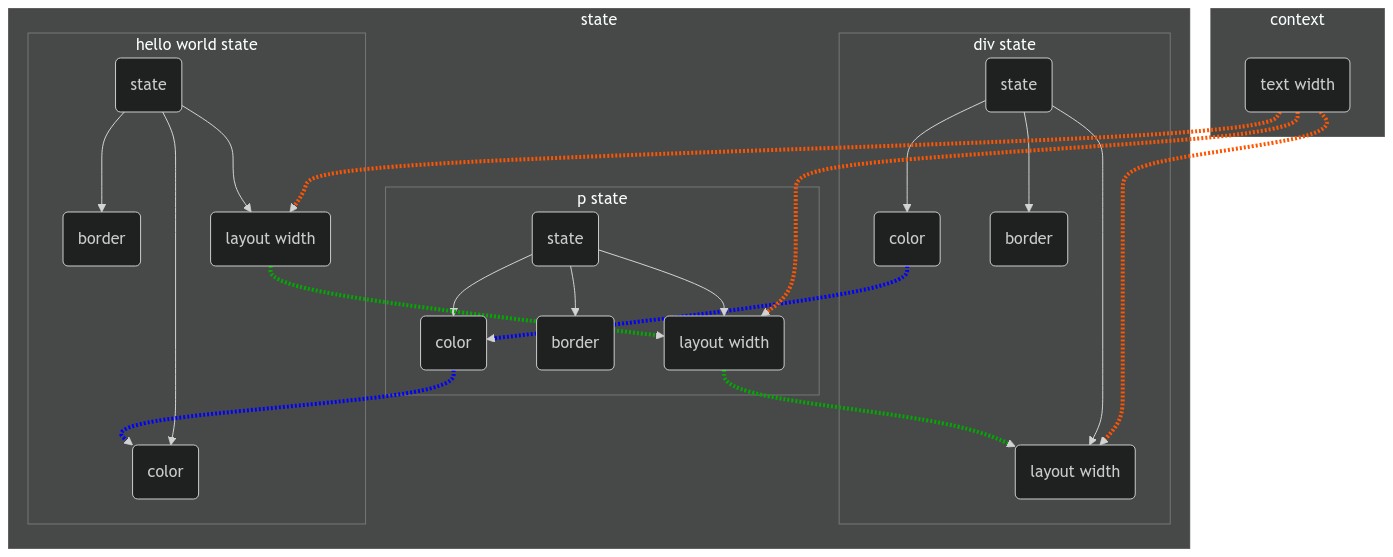

In the following diagram arrows represent dataflow:

To help in building a Dom, native-core provides four traits: State, ChildDepState, ParentDepState, NodeDepState, and a RealDom struct. The ChildDepState, ParentDepState, and NodeDepState provide a way to describe how some information in a node relates to that of its relatives. By providing how to build a single node from its relations, native-core will derive a way to update the state of all nodes for you with #[derive(State)]. Once you have a state you can provide it as a generic to RealDom. RealDom provides all of the methods to interact and update your new dom.

use dioxus_native_core::node_ref::*; use dioxus_native_core::state::{ChildDepState, NodeDepState, ParentDepState, State}; use dioxus_native_core_macro::{sorted_str_slice, State}; #[derive(Default, Copy, Clone)] struct Size(f32, f32); // Size only depends on the current node and its children, so it implements ChildDepState impl ChildDepState for Size { // Size accepts a font size context type Ctx = f32; // Size depends on the Size part of each child type DepState = Self; // Size only cares about the width, height, and text parts of the current node const NODE_MASK: NodeMask = NodeMask::new_with_attrs(AttributeMask::Static(&sorted_str_slice!(["width", "height"]))).with_text(); fn reduce<'a>( &mut self, node: NodeView, children: impl Iterator<Item = &'a Self::DepState>, ctx: &Self::Ctx, ) -> bool where Self::DepState: 'a, { let mut width; let mut height; if let Some(text) = node.text() { // if the node has text, use the text to size our object width = text.len() as f32 * ctx; height = *ctx; } else { // otherwise, the size is the maximum size of the children width = children .by_ref() .map(|item| item.0) .reduce(|accum, item| if accum >= item { accum } else { item }) .unwrap_or(0.0); height = children .map(|item| item.1) .reduce(|accum, item| if accum >= item { accum } else { item }) .unwrap_or(0.0); } // if the node contains a width or height attribute it overrides the other size for a in node.attributes(){ match a.name{ "width" => width = a.value.as_float32().unwrap(), "height" => height = a.value.as_float32().unwrap(), // because Size only depends on the width and height, no other attributes will be passed to the member _ => panic!() } } // to determine what other parts of the dom need to be updated we return a boolean that marks if this member changed let changed = (width != self.0) || (height != self.1); *self = Self(width, height); changed } } #[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, Default)] struct TextColor { r: u8, g: u8, b: u8, } // TextColor only depends on the current node and its parent, so it implements ParentDepState impl ParentDepState for TextColor { type Ctx = (); // TextColor depends on the TextColor part of the parent type DepState = Self; // TextColor only cares about the color attribute of the current node const NODE_MASK: NodeMask = NodeMask::new_with_attrs(AttributeMask::Static(&["color"])); fn reduce( &mut self, node: NodeView, parent: Option<&Self::DepState>, _ctx: &Self::Ctx, ) -> bool { // TextColor only depends on the color tag, so getting the first tag is equivilent to looking through all tags let new = match node.attributes().next().map(|attr| attr.name) { // if there is a color tag, translate it Some("red") => TextColor { r: 255, g: 0, b: 0 }, Some("green") => TextColor { r: 0, g: 255, b: 0 }, Some("blue") => TextColor { r: 0, g: 0, b: 255 }, Some(_) => panic!("unknown color"), // otherwise check if the node has a parent and inherit that color None => match parent { Some(parent) => *parent, None => Self::default(), }, }; // check if the member has changed let changed = new != *self; *self = new; changed } } #[derive(Debug, Clone, PartialEq, Default)] struct Border(bool); // TextColor only depends on the current node, so it implements NodeDepState impl NodeDepState<()> for Border { type Ctx = (); // Border does not depended on any other member in the current node const NODE_MASK: NodeMask = NodeMask::new_with_attrs(AttributeMask::Static(&["border"])); fn reduce(&mut self, node: NodeView, _sibling: (), _ctx: &Self::Ctx) -> bool { // check if the node contians a border attribute let new = Self(node.attributes().next().map(|a| a.name == "border").is_some()); // check if the member has changed let changed = new != *self; *self = new; changed } } // State provides a derive macro, but anotations on the members are needed in the form #[dep_type(dep_member, CtxType)] #[derive(State, Default, Clone)] struct ToyState { // the color member of it's parent and no context #[parent_dep_state(color)] color: TextColor, // depends on the node, and no context #[node_dep_state()] border: Border, // depends on the layout_width member of children and f32 context (for text size) #[child_dep_state(size, f32)] size: Size, }

Now that we have our state, we can put it to use in our dom. Re can update the dom with update_state to update the structure of the dom (adding, removing, and changing properties of nodes) and then apply_mutations to update the ToyState for each of the nodes that changed.

fn main(){ fn app(cx: Scope) -> Element { cx.render(rsx!{ div{ color: "red", "hello world" } }) } let vdom = VirtualDom::new(app); let rdom: RealDom<ToyState> = RealDom::new(); let mutations = dom.rebuild(); // update the structure of the real_dom tree let to_update = rdom.apply_mutations(vec![mutations]); let mut ctx = AnyMap::new(); // set the font size to 3.3 ctx.insert(3.3f32); // update the ToyState for nodes in the real_dom tree let _to_rerender = rdom.update_state(&dom, to_update, ctx).unwrap(); // we need to run the vdom in a async runtime tokio::runtime::Builder::new_current_thread() .enable_all() .build()? .block_on(async { loop{ let wait = vdom.wait_for_work(); let mutations = vdom.work_with_deadline(|| false); let to_update = rdom.apply_mutations(mutations); let mut ctx = AnyMap::new(); ctx.insert(3.3); let _to_rerender = rdom.update_state(vdom, to_update, ctx).unwrap(); // render... } }) }

Layout

For most platforms, the layout of the Elements will stay the same. The layout_attributes module provides a way to apply HTML attributes to a stretch layout style.

Conclusion

That should be it! You should have nearly all the knowledge required on how to implement your own renderer. We're super interested in seeing Dioxus apps brought to custom desktop renderers, mobile renderers, video game UI, and even augmented reality! If you're interested in contributing to any of these projects, don't be afraid to reach out or join the community.