Components and Properties

In Dioxus, components are simple functions that encapsulate your UI's presentation, state, and interactions. As your apps grow in size, consider combining shared functionality into smaller reusable components. Modular components make working in large teams easier, prevent annoying bugs, and enable better code reuse across all platforms.

Defining Components

In its simplest form, a component is a function that returns an Element. For example, the base app component:

fn app() -> Element { rsx! { "hello world!" } }

If you want to use a component from another component, then you must annotate the function with the #[component] macro. This macro provides essential metadata to the RSX macro, allowing function arguments to become fields in the component's properties. Your function must meet the following requirements:

- Either start with a capital letter (

MyComponent) or contain an underscore (my_component) - Take arguments that implement

PartialEqandClone - Return an

Element

We call the arguments a component takes its properties. Properties are used to pass data into the component, similar to how you would pass arguments to a function.

For example, we can define a simple component that takes a name property and renders a greeting:

#[component] pub fn MyComponent(name: String) -> Element { rsx! { div { h3 { "Hello, {name}!" } } } }

Hello, world!

Using Components in RSX

Once you have defined a component, you can use it in your RSX markup just like any other element:

rsx! { MyComponent { name: "World" } }

Hello, World!

Although components are defined as functions, they should not be called like regular functions. When you use a component in RSX, Dioxus will create a new instance of the component that controls its own state and lifecycle.

Component Properties

A component's properties is the object passed to the component when it renders. These properties are similar to a function's arguments - this is why the property fields are defined as function arguments in components. In some cases, you might find it useful to extract the component properties to a separate struct. Instead of defining properties inline, we can simply use an argument named "props" and then define the props in an accompanying struct.

#[derive(PartialEq, Clone, Props)] struct CardProps { title: String, content: String } #[component] fn Card(props: CardProps) -> Element { rsx! { h1 { "{props.title}" } span { "{props.content}" } } }

When we extract properties into a struct, we need to make sure the struct implements three required traits:

PartialEq: used to identify if a component needs to be rerenderedClone: on each render, the properties object is clonedProps: derives thePropertiestrait which Dioxus uses for rendering and building

Each of these bounds has implications for how we structure our component's properties.

PartialEq

PartialEq is used by the Dioxus runtime to determine if a component's properties have changed due to some user action. Because components are called by other components, small changes to properties up the component tree can result in a cascade of work for the Dioxus runtime. The PartialEq implementation is used to minimize the amount of work the Dioxus runtime needs to do when reacting to these changes.

For advanced use cases, it can be worth customizing a properties' PartialEq implementation for performance. For example, we might want to compare large datasets just by their ID, not their actual contents. In these cases, we'd manually implement the PartialEq trait to skip the dataset equality check:

#[derive(Clone, Props)] struct DatasetViewer { id: Uuid, contents: Vec<u8> } impl PartialEq for DatasetViewer { fn eq(&self, other: &Self) -> bool { self.id.eq(&other.id) } }

Many Dioxus utilities use comparison-by-pointer instead of comparison-by-contents to improve performance.

Clone

The Clone bound is a particularly interesting requirement for component properties. The Dioxus component tree architecture is designed around an idea called "unidirectional data flow." This is a design pattern that prevents components down the component tree from modifying their input properties. By preventing these accidental mutations, user interfaces generally have fewer bugs. Rust itself generally solves this problem its borrow checker system, but the borrow checker does not work well with asynchronous work which is quite prevalent in app development.

Generally, it's fine to .clone() most component properties, but some objects might be too expensive to clone and negatively impact performance. In most cases, you can simply wrap the value in the [ ReadSignal] wrapper type and the object will be automatically wrapped in a smart pointer:

// previously... struct CardProps { content: String } // with ReadSignal: struct CardProps { content: ReadSignal<String> }

Fortunately, there are no code changes required on the calling side:

rsx! { CardProps { content: query.content() } }

Note that ReadSignal is not the only smart pointer available. The Rust smart pointers (Arc, Rc) also make clones cheaper as can a custom Clone implementation.

Props

The Props derive macro implements the Properties trait for the properties object. This trait and its implementation are an implementation detail in Dioxus and not generally meant to be implemented manually. The Props derive is useful because it derives a strongly typed builder for the Properties. We can even use this builder outside RSX:

let props = CardProps::builder().content("body".to_string()).build();

The #[component] macro

Properties can be modified to accept a wider variety of inputs than a normal function argument. We don't cover all of the details here, but you can find information in the component macro documentation.

For example, the Dioxus Router Link component uses the modifiers extensively:

/// The properties for a [`Link`]. #[derive(Props, Clone, PartialEq)] pub struct LinkProps { /// The class attribute for the `a` tag. pub class: Option<String>, /// A class to apply to the generate HTML anchor tag if the `target` route is active. pub active_class: Option<String>, /// The children to render within the generated HTML anchor tag. pub children: Element, /// When [`true`], the `target` route will be opened in a new tab. /// /// This does not change whether the [`Link`] is active or not. #[props(default)] pub new_tab: bool, /// The onclick event handler. pub onclick: Option<EventHandler<MouseEvent>>, /// Whether the default behavior should be executed if an `onclick` handler is provided. /// /// 1. When `onclick` is [`None`] (default if not specified), `onclick_only` has no effect. /// 2. If `onclick_only` is [`false`] (default if not specified), the provided `onclick` handler /// will be executed after the links regular functionality. /// 3. If `onclick_only` is [`true`], only the provided `onclick` handler will be executed. #[props(default)] pub onclick_only: bool, /// The rel attribute for the generated HTML anchor tag. /// /// For external `a`s, this defaults to `noopener noreferrer`. pub rel: Option<String>, /// The navigation target. Roughly equivalent to the href attribute of an HTML anchor tag. #[props(into)] pub to: NavigationTarget, #[props(extends = GlobalAttributes)] attributes: Vec<Attribute>, }

You can use the #[props()] attribute on each field to modify properties your component accepts:

#[props(default)]- Makes the field optional in the component and uses the default value if it is not set when creating the component.#[props(!optional)]- Makes a field with the typeOption<T>required.#[props(into)]- Converts a field into the correct type by using the [Into] trait.#[props(extends = GlobalAttributes)]- Extends the props with all the attributes from an element or the global element attributes.

Props also act slightly differently when used with:

Option<T>- The field is automatically optional with a default value ofNone.ReadOnlySignal<T>- The props macro will automatically convertTintoReadOnlySignal<T>when it is passed as a prop.String- The props macro will accept formatted strings for any prop field with the typeString.children: Element- The props macro will accept child elements if you include thechildrenprop.EventHandler<T>enforces closures

Note that these attributes work both for struct-based property definitions as well as inline definitions:

#[component] fn Link( /// When [`true`], the `target` route will be opened in a new tab. #[props(default)] new_tab: bool, /// The navigation target. Roughly equivalent to the href attribute of an HTML anchor tag. #[props(into)] to: NavigationTarget, ) -> Element { // ... }

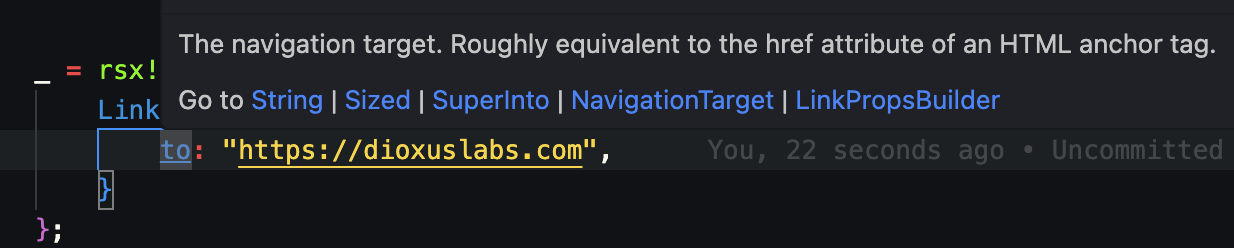

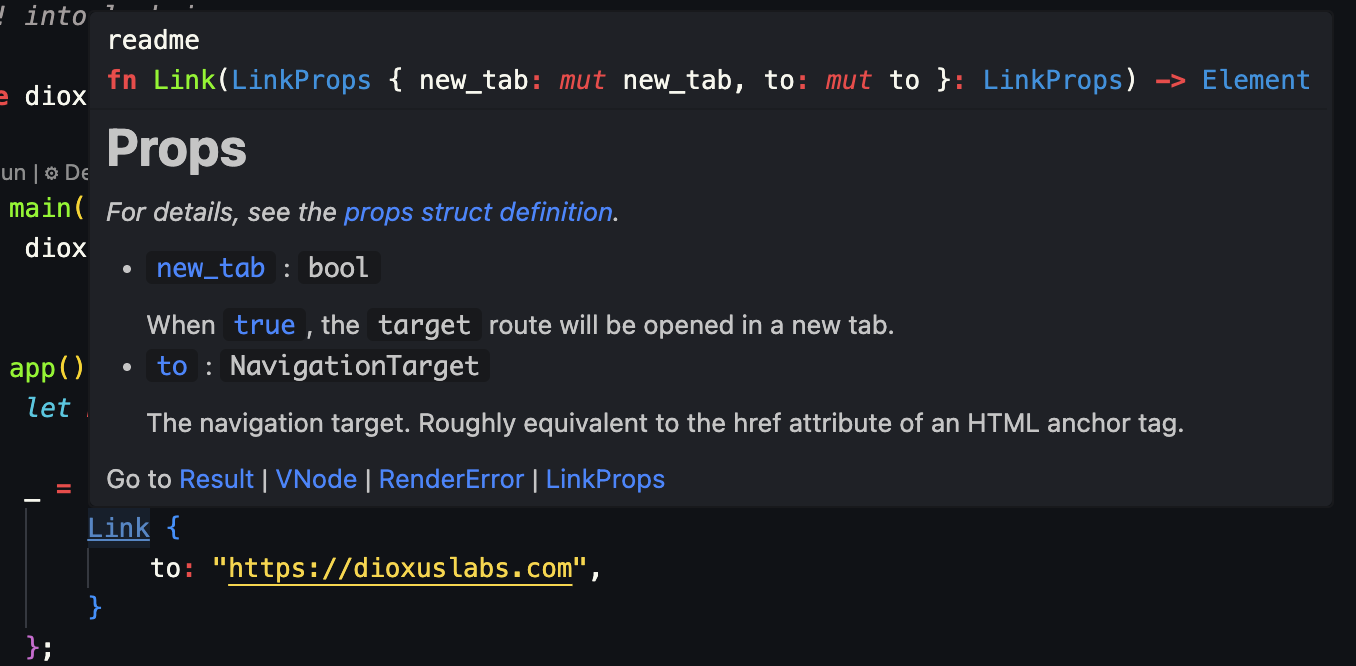

Because documentation comments are parsed by the #[component] macro, they become available as inline documentation when calling the component:

The docs on the component are also available when hovering its use:

Spreading Props

For more composability, we can create a component's properties manually and then pass them directly using Rust's spread syntax with ..some_props.

let props = CardProps::lorem_ipsum(); rsx! { Card { ..props } }

This mechanism behaves similar to Rust's struct spreading, allowing you to override various fields of the spread, enabling default and overrides:

let props = CardProps::lorem_ipsum(); rsx! { Card { title: "Chapter 1", ..props } }

Children

Properties have a special field called "children" that contain a component's child elements. For example, we can build a wrapper component that wraps its children in a red div. This component takes a special argument named "children" which is an Element that is used in RSX expressions.

#[component] fn RedDiv(children: Element) { rsx! { div { background_color: "red", {children} } } }

When calling the component, we can simply add nested children like an element:

rsx! { RedDiv { h1 { "Lorem Ipsum Dolor" } p { "..." } } }